Courtaud & The Paris Wolf Attacks

"This is the story of Great Courtaud, the king wolf; The wolf that ruled all Central France like a ferocious despotic monarch; the wolf that drove a thousand men in flight before him; the wolf that shut up all Paris in a state of siege for three hard years of snow; the wolf that sent King Charles into poltroon hiding behind his castle walls of stone; the wolf that every day devoured a man as a dog might maul his daily ration bone."

The story and accompanying quotes are taken from the book "Mainly About Wolves" by Ernest Thompson Seton (Chapter XVII: Courtaud, The King Wolf of France.)

COURTAUD

At the time of Courtaud's appearance, France struggled on several fronts: English armies had overtaken Normandy; Burgandy, Brittany, Luxembourg and Provenance were under the control of warlords; and the peasantry suffered through hunger and disease.

Paris at that time was an 'island' centered in the Seine, surrounded by the river on all sides and protected by walls of stone. It was the biggest trading market in France and herds of cattle were taken there daily under armed guard.

Paris at that time was an 'island' centered in the Seine, surrounded by the river on all sides and protected by walls of stone. It was the biggest trading market in France and herds of cattle were taken there daily under armed guard.

Several circumstances helped especially attract wolves at that time: constant cattle being driven to Paris; and a nearby rugged glen, cleared of all trees - cut for wood fuel - which had become a veritable stronghold for wolves which dogs, horses and even men refused to enter.

They were attacked on route, and the three family members devoured. Jean Dubois put up a courageous fight in an effort to save his family, but was outnumbered by the wolves and easily killed.

In January, the wolves became more desperate. Travel had decreased in the winter months and the scent of food and prey emanated from the city, which brought them increasingly closer to the gates.

Leading the pack was Courtaud. Men rushed to the gates to trap the wolves within, as others attempted to fell them with arrows. Courtaud seemed to instinctively understand the trap when he saw the gates beginning to swing shut, and ran through them while there was still enough space to pass.

But as he passed the portcullis - it dropped, and one of its sharp edges caught his tail. He managed to flee but his tail was reduced to a stump, and from that time on he was called Courtaud [bobtail] due to this recognizable feature.

This attack - in the winter of 1428 - made Courtaud and the wolves wary of approaching the city's walls, and so for a time they kept their distance. Cattle were kept within stables and the gentlefolk in the nearby countryside were brought to Paris. Any herds brought into the city were kept small in number and well-guarded.

The summer and autumn of 1428 continued with more of the same: cattle and travellers on the outskirts of the city picked off continually. From January to March, Paris was shut up and surrounded by the hungry bands of wolves. When the snow began to melt, horsemen dispatched from the King brought forth a food supply from Provence. Courtaud readied to attack the convoy, but was warned off by bells and trumpets; the convoy reached the city without incident.

During the summer of 1429, both civil and foreign wars took their toll on France; hundreds died and were left as food for the wolves.

There was a city house which belonged to a dowager from a noble family - The Countess of Miel. She had built a private gallery - a secret passage - over the river which connected to her residence. In this way, she discreetly had male company join her in her private room. Midway through the room was a hidden trap door which could be opened when a spring was released.

By February, deepening snow and hunger made the wolves bolder; they were visible nearly every day from the watch tower, but kept out of range of any arrows. In the morning, wolf tracks on the frozen Seine showed that they had spent the night prowling around the city walls seeking entry.

Finally one night, the wolves found entrance through a three foot gap between the frozen river and a protective grille.

The city was horrified by events; among the dead were priests and even the Archbishop. Fed up, a captain of the city guard named Boisselier decided to take charge. He reportedly said:

"Are Frenchmen down so low, so helpless turned, that wolves may enter the chief city when they will, and banquet in the sacred place on human flesh and blood, and leave unharmed? This is their challenge, the challenge I accept. And on that very spot would I elect to meet the king wolf, each to each. This is my plan, if you permit O King!"

The king assented. Boisselier called a council together and formed a plan, the details of which were:

He also ordered that no one was to shoot or shout at the wolves, or make any noise which might dissuade them. For the following four nights wolves came and investigated, leaving hastily; Courtaud was not with them.

For several more days wolves continued to come, and after ten days Boisselier ordered twenty beeves to be slaughtered in front of the Cathedral and the Parvis in front to be covered with blood and offal. At last this did the trick, and that very night the wolves arrived in number. Boisselier himself closed the gate, trapping them within the city.

In the morning, citizens of the city crowded around the windows, walls and roofs nearby to watch the showdown unfold.

COURTAUD

At the time of Courtaud's appearance, France struggled on several fronts: English armies had overtaken Normandy; Burgandy, Brittany, Luxembourg and Provenance were under the control of warlords; and the peasantry suffered through hunger and disease.

"At such a time it was that the pirate bands of ravening wolves, no longer held in check ... swept from the woods across the desolated fields, and raided towns and hamlets ... In all the lowlands of the Loire, the sheep were gone -- devoured, destroyed. The cattle that were left were herded by peasants and defended with such weapons as were at hand. By night, they were safe corralled in barns or high stockades.

But ever the number dwindled, and the packs of hungry wolves grew bigger and bolder. Each village had its skift of wolves that lurked all day in wait for stragglers - men or kine - or boldly came by night to scour the streets."

Paris at that time was an 'island' centered in the Seine, surrounded by the river on all sides and protected by walls of stone. It was the biggest trading market in France and herds of cattle were taken there daily under armed guard.

Paris at that time was an 'island' centered in the Seine, surrounded by the river on all sides and protected by walls of stone. It was the biggest trading market in France and herds of cattle were taken there daily under armed guard.Several circumstances helped especially attract wolves at that time: constant cattle being driven to Paris; and a nearby rugged glen, cleared of all trees - cut for wood fuel - which had become a veritable stronghold for wolves which dogs, horses and even men refused to enter.

"Here it was known that many wolves had their dens, and each year new litters of cubs were born, to be a terror on the roads that led to the great city. It was many generations before the place was cleaned up; and the only memory of its savage denizens left today is the name, the same but shortened, that attaches to the place - the Louvre."According to Monkish chroniclers, Courtaud ... "first appeared in full stature and development in the summer of 1427. He was readily distinguished from afar by his magnificent size and bearing, for he was a giant among wolves...

"He was often alone, and had a marvellous gift for discovering and avoiding men with bows and arrows. Of these he was afraid; but for herdsmen, armed with spears or billhooks, he had an utter contempt. He would rush past such helpless guardians, cut down some yearling, hamstringing it first, then later cut its throat. If the herdsmen hurried on with the remaining cattle, he let them go; if they strove to fight him off, he turned his savage fury on them, and quickly claimed one or more of the human victims.

This happened many times that year; and soon the accepted policy of the herdsmen was this: 'Let him have one beef or he will get you'; that is, pay the toll to the robber, so that he may spare your life."It carried on this way until an incident with the Dubois family - three peasants on their way to Paris to sell sheep. They took precautions by carrying the sheep in a horse-driven cart and hanging tins, bells and other noise-makers from the harness and wagon.

They were attacked on route, and the three family members devoured. Jean Dubois put up a courageous fight in an effort to save his family, but was outnumbered by the wolves and easily killed.

"Thenceforth one and all were man-eaters of fanatical obsession. Not only was the big wolf a man-eater, but his leadership was so forceful that the habit spread; and in a few months, the dreadful fact was known that the wolves of the Louvre Forest would leave the herd untouched, and feed by preference on the flesh of the human guardians...

... One historian tells us more exactly that in the first month of that calamitous winter ... fourteen persons were killed and devoured by the wolves; and in each case, the wolves had refused the counter-allurement of beef.

The giant wolf was seen in many of these onslaughts, and was believed to be the instigator of them all. He seemed to possess a charmed life, for all attempts to injure him were vain. There could be no longer any doubt that his headquarters was Le Louvre. There, close to the Paris gates, he and his bandit crew could at any time attack the coming and going groups of travellers or kine.."The wolves generally attacked by day since the gates of the city were shut and barred at sunset. Courtaud avoided the walls and towers since men shot crossbows at the wolves from atop and sometimes succeeded in bringing one down.

In January, the wolves became more desperate. Travel had decreased in the winter months and the scent of food and prey emanated from the city, which brought them increasingly closer to the gates.

"Food was scarce in Paris now; and when a band of cattle was announced as coming fast with mounted guards around them, the city was astir. The great gate at the bridge was thrown wide open, and the beef herd huddled through with every haste. But the wolves had gathered in the rear, gaining courage from their numbers; and headed by the king wolf, they charged on the wake of the herd.

There was a time of confusion, terror, and stampede. All aimed to reach the shelter of the gate. The cattle went clattering through the main streets, the foot-folk fled into their homes, the warders rushed to their towers. The wolves came surging into the city by the open gate, following after the beef herd and their guards. There were some men down, some wolves were pierced by arrows, a score of officials were yelling their commands. "

Leading the pack was Courtaud. Men rushed to the gates to trap the wolves within, as others attempted to fell them with arrows. Courtaud seemed to instinctively understand the trap when he saw the gates beginning to swing shut, and ran through them while there was still enough space to pass.

But as he passed the portcullis - it dropped, and one of its sharp edges caught his tail. He managed to flee but his tail was reduced to a stump, and from that time on he was called Courtaud [bobtail] due to this recognizable feature.

This attack - in the winter of 1428 - made Courtaud and the wolves wary of approaching the city's walls, and so for a time they kept their distance. Cattle were kept within stables and the gentlefolk in the nearby countryside were brought to Paris. Any herds brought into the city were kept small in number and well-guarded.

"As the snow grew deeper and food grew scarcer, the wolves grew more hungry and more daring. A single traveller, yes even a small group of travellers, had no chance of escape if they entered the wolf-infested belt of woods that stretched around Paris."

As for Courtaud: "Many times he was seen by watchers and by travelling troops of mounted men; but he seemed immune from all attack, and the terror of his name was on all that part of France. The common salutation of the day to a traveller going forth from Paris to some far point was: 'Well, Goodbye; God bless you, and see that Courtaud does not get you'."

The summer and autumn of 1428 continued with more of the same: cattle and travellers on the outskirts of the city picked off continually. From January to March, Paris was shut up and surrounded by the hungry bands of wolves. When the snow began to melt, horsemen dispatched from the King brought forth a food supply from Provence. Courtaud readied to attack the convoy, but was warned off by bells and trumpets; the convoy reached the city without incident.

During the summer of 1429, both civil and foreign wars took their toll on France; hundreds died and were left as food for the wolves.

There was a city house which belonged to a dowager from a noble family - The Countess of Miel. She had built a private gallery - a secret passage - over the river which connected to her residence. In this way, she discreetly had male company join her in her private room. Midway through the room was a hidden trap door which could be opened when a spring was released.

"Below the trap-door was a chute bristling with sharp-set knives; and twenty feet below was the surging river flood...

Awaiting a lover the high-born lady was, on that fair moonlit night in the autumn of the year. Peering from her casement she saw ... in view - a wolf, a monster wolf, a bob-tailed wolf. In a flash, the wily dame conceived a plot. From the larder, with her own hands, she bore a chine of beef ...

... the outer door was open wide. She rubbed the threshold with the meat, she dragged the bloody mass along to the upper door; then from a peephole, watched.

The great wolf sniffed and sniffed. He cautiously drew near ... and when the countess saw the dim grey bulk had passed into the snare, she touched the spring. The was nothing but a click, but that was a warning click. The king wolf was alert. In a moment, he sensed a trap ... with one great bound, he cleared the treacherous place, made out the door and away, unharmed - and wiser than he ever was before."The difficult winter months came and plague visited the city, blanketing it in gloom. The corpses were disposed of by hurling them from the towers for the wolves to eat. It was hoped that the plague-ridden flesh would spread the disease among the wolves, but it did not. Instead, "it confirmed the wolves in their love for man-meat, and proclaimed the city more than ever a place of feasting and wolf joy."

By February, deepening snow and hunger made the wolves bolder; they were visible nearly every day from the watch tower, but kept out of range of any arrows. In the morning, wolf tracks on the frozen Seine showed that they had spent the night prowling around the city walls seeking entry.

Finally one night, the wolves found entrance through a three foot gap between the frozen river and a protective grille.

"They passed through the gap under the water gate, and by a dozen devious routes appeared in the great Parvis before the Cathedral. A band of holy men were leaving their duties in the chancel to seek their homes, when down on them the wolf band swept. Wholly taken by surprise were the victims, and wholly unarmed. In twenty minutes all were dead. The wolf pack revelled for an hour; then gorged with human flesh, they fled by the river gap that let them in. Before the terrified burghers could spread the alarm and assemble worth-while help, forty human beings were killed and partly devoured in this dreadful raid. Not a single wolf was slain."

The city was horrified by events; among the dead were priests and even the Archbishop. Fed up, a captain of the city guard named Boisselier decided to take charge. He reportedly said:

"Are Frenchmen down so low, so helpless turned, that wolves may enter the chief city when they will, and banquet in the sacred place on human flesh and blood, and leave unharmed? This is their challenge, the challenge I accept. And on that very spot would I elect to meet the king wolf, each to each. This is my plan, if you permit O King!"

The king assented. Boisselier called a council together and formed a plan, the details of which were:

"For two weeks, no man or beast might leave or enter Paris; no garbage be cast over the walls, so that every source of food should be taken from the wolves. The iron grille at the King's landing should be raised and left three feet above the ice which still was strong, and again at normal level.

All garbage was to be scattered on the Parvis or square of Notre Dame. All beeves that were killed for food were to be killed in that square, and the offal scattered about. A high gate or wall was to be built across all streets leading into the Parvis; an open way from the King's landing to the Parvis, controlled by a gate that could be closed from an upper window. The entrails of a beef were to be dragged from the far shore across the ice to the King's landing, thence up the alley to the Parvis."

He also ordered that no one was to shoot or shout at the wolves, or make any noise which might dissuade them. For the following four nights wolves came and investigated, leaving hastily; Courtaud was not with them.

For several more days wolves continued to come, and after ten days Boisselier ordered twenty beeves to be slaughtered in front of the Cathedral and the Parvis in front to be covered with blood and offal. At last this did the trick, and that very night the wolves arrived in number. Boisselier himself closed the gate, trapping them within the city.

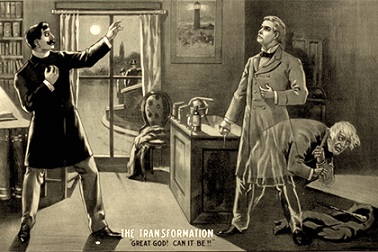

In the morning, citizens of the city crowded around the windows, walls and roofs nearby to watch the showdown unfold.

"... Boisselier gave the word, and archers from every vantage point let fly their winged shafts. Wolf after wolf went down; but few fell struck by a single bolt. The wounded were more than the dead, and many a wolf drew with his teeth the shaft and then renewed the hopeless fight...

And still the wolves raced round. Scores were dead before an hour had passed. Many more were wounded, and a great brown mass was surging round untouched."In the centre of the square was a fountain which Courtaud lay under, protected from arrows and harm; he sat calmly, surrounded by a group of wolves which were also protected. By noon, hundreds of wolves had been killed and lay on the ground. Courtaud remained alive, along with dozens of others.

Boisselier, joined by a group of skilled fighters, descended by ladders into the area; he saluted the King, then marched on the wolves. On the orders of the King, a chief huntsman opened a side door and brought in a great pack of wolfhounds, equal in number to the wolves.

"Then came a scene that all the world would thrill to see. The king wolf rose, gave one great gathering howl, the war-cry of his race; and at the dogs they went. The battle lasted half an hour, and every dog went down. Great Courtaud slew a dozen in that fray. And not a wolf was slain; but few were hurt."Next, Boisselier and the guardsman attacked with long sharp spears. Many wolves went down, but many men were also hurt and five had their throats slashed.

"Cheers from the crowded roofs and the royal banner waving inspired the men. They pushed the fight. With their long lances, they reached under the fountain; they speared the wolves, they killed near all. But some, with Courtaud in the lead, broke away and dashed for another haven, the doorway of the church. Here, under the stone arcade, they faced about - Courtaud and five - with a ring of men around them. A mauling gruelling fight - men slashed in limb and neck.

Wolf after wolf went down, till only one was left - the great grim king. Then Boisselier, a valiant man, a lover of an even fight, cried out: 'Hold back! Since only he is left and challenged me, we'll settle this in single fight.' And charged with his lance as knight against knight.

The great wolf reared and sprang to meet him; the lance went through his chest. But he sprang with all his force, slid up the lance, and the man went down. And Courtaud, with his fearful slashing fangs, cut through the leather jerkin, ripped the throat-strap of his helm, and tore his throat out as he lay. Down, down, they fell at grips, their red lives gushed, the great grim wolf and the brave strong man. They lay in death together."Bells rang out from the Cathedral, followed by the churches. The three hundred wolves were laid down in rows, and on a red-and-black draped platform Courtaud was displayed for all to witness. A herald bared his trumpet before the King, and cried to all 'round that the great wolf was dead for all to see.