Gilles de Rais/ "Bluebeard"

The most informative book to date on Gilles de Rais is his biography "The Real Bluebeard" written by Jean Benedetti. Its subject matter is summarized below.During his time

The environment Gilles de Rais was born into was one of feudal violence and uncertainty. The Hundred Years War was ongoing; central government had essentially collapsed and laws could not be enforced.

Charles VI ruled but was insane, which created an intense power struggle around him. Nearby was Brittany, which had never been a part of France and vacillated between France and England. There was also the Burgundy, which periodically negotiated with the English.

France was technically fighting England, but virtually in a state of civil war. During temporary periods of peace, people would divide into factions that became marauding bands: pillaging, stealing, raping and killing.

France was technically fighting England, but virtually in a state of civil war. During temporary periods of peace, people would divide into factions that became marauding bands: pillaging, stealing, raping and killing."The class of warrior-nobles, of which Gilles was to become a member, fought to hold on to their possessions, and pursued their own private war-games to the detriment of their country and its populace. Indeed the English and French nobility were so closely intermarried and interconnected that it is hardly possible to talk of the two sides in terms of nationality at all.The Catholic church played an integral part in politics and daily life, but was corrupt: clergy openly lived with mistresses and their children.

The nobility amused themselves with feasts, games, entertainment and romantic ideas of 'chivalry' and 'maidenhood' which bore no connection to the realities around them. They also feuded with one another: taking the lapse of royal control as an opportunity to kill rivals or kidnap them for ransom.

Circumstances of birth

The Duke of Brittany wanted her lands, especially along the border, and so she began to search for an heir.

She sought out her second cousin Guy de Laval, and agreed to pass the inheritance to him if he took on the 'de Rais' name. An agreement was signed, but she later changed her mind and disinherited him.

Jeanne decided to give her fortune to her only other living relative Catherine de Machecoul. Catherine was a widow with only one son, Jean de Craon.

Angered by the disinheritance, Guy de Laval sued. Being a wily, scheming character, Jean de Craon proposed that his daughter Marie marry Guy, thereby uniting the family and resolving the dispute.

Guy (now de Rais) and Marie married on February 5, 1404. Their child was born in under a year, and baptized Gilles.

Childhood & Adolescence

Gilles spent his early years with his wet-nurse and her son Jean. In 1407, at three years old, his brother Rene de la Suze was born. (By all accounts they were never close and disliked each other.)

He received instruction from two priests, one with a degree in Law. He was educated in military tactics, religion, and the Latin language. He lived in luxury; immensely spoiled and received no discipline (servants and tutors could not provide it). His parents were generally absent, kept continually occupied by the court and social events.

In 1415, his father died: he was gored by a wild boar while out hunting. As he lay dying, he stipulated his will and appointed a close personal friend as the children's guardian. Circumstances regarding Gilles' mother can't be stated with certainty, she likely died before or around that time.

That same year Jean de Craon's only son died in battle, leaving Gilles the heir to all the Rais, Laval, and Craon combined wealth and property. His grandfather Jean de Craon pushed himself into becoming legal guardian and took over the care of his grandchildren (their father's friend gave in without argument).

Jean de Craon began to search for a wife for Gilles, who was twelve years old. He found two suitable matches with dowries, but was foiled each time and the contracts came to nothing.

In 1419, a raging feud erupted between two powerful families. The Duke of Brittany's family (de Monfort) had been quarreling with the Penthievre family for a century. During which time, Jean de Craon's family had always supported the Penthievres, but - assessing the political situation - he switched his allegiance to the Duke of Brittany. This caused the Penthievre faction to ravage the de Rais land and estates (after taking the Duke hostage).

Jean de Craon was part of the faction which helped to save the Duke, and so he was rewarded with income from his vanquished foes' lands. This helped him earn prestige, and Gilles was subsequently introduced to some of the most important political families of the time.

"Gilles and his grandfather returned to their castles to resume normal life. What their 'normal' life consisted of Gilles indicated in his later confessions: the unbridled satisfaction of all his whims and fancies accompanied by excessive eating and drinking at table. The pattern of their lives seems to have been a round of good living occasionally punctuated by marauding raids and sorties."Jean de Craon again turned his thoughts to Gilles' marriage and found a suitable bride: Catherine de Thouars. While her father was absent suitors bombarded her and encamped outside her castle. On November 22, 1420 news reached Gilles that Catherine's father was dying of fever. He set out with a group of men and kidnapped Catherine; on November 30, they were married in a remote chapel.

The Bishop of Angers declared the marriage null and void, so Jean de Craon was forced to send an envoy to Rome to plead the case; he was also forced to concede some of Catherine's lands to her relatives as a sort of informal bribe. Negotiations lasted two years and the marriage finally received the Pope's approval. A month later the couple were remarried by the Bishop of Angers in a formal ceremony before a congregation. During this time, Jean de Craon's wife had died, so for good measure he married Catherine's grandmother.

At age 20, Gilles legally took control over his fortune and affairs. Although his grandfather had amassed him a fortune and connived to reach high status, he no longer had any control over his grandson and could only advise from thereon.

Charles VII

The Treaty of Troyes had been signed in 1420 - making English Henry V the official heir with England and France a 'double-kingdom'.

The Dauphin (Charles VII) was in a difficult position. His mother had declared him a bastard and his father disinherited him. Part of his kingdom was in English hands; the Duke of Burgundy sided with the English, while the Duke of Brittany couldn't decide whom to support.

His mother-in-law Yolande d'Aragon was an ambitious woman who wanted the Duke of Brittany's undivided loyalty. To gain it, her plan was to marry her son Louis III to his daughter Isabelle. To this end, she turned to Jean de Craon to use his skills in order to negotiate the marriage and a treaty of alliance. He was successful in his endeavor and the marriage contract was signed on October 7, 1425. Gilles was present, and this would have been his first contact with royalty and introduction to royal circles.

That same year, Charles VII had started preparations for the renewal of the Hundred Years War. By 1427, Yolande d'Aragon had appointed Jean de Craon Lieutenant-General of Anjou; his task was the levying and commanding of troops. As he was over seventy years old, the task was his in name only - the effort fell to Gilles.

Gilles organized five companies which campaigned successfully against the English during the spring and summer - proving himself and gaining a fine reputation.

Year with Joan of Arc

“Of all the people who influenced Gilles’ life, Joan is the most controversial and the most enigmatic …

… But the fact remains that for the rest of the year 1929 Joan and Gilles’ life are the same and it was through his association with her that he achieved fame and glory.”

The Hundred Years War was in a stalemate while internal squabbling and politicking carried on in the French court. Taking advantage, the English marched unimpeded to the city of Orleans and began a siege.

In February 1429 the French army counter-attacked but lost in a total, humiliating defeat.

It was then announced that 'Joan the Maid' was coming to meet the king. Joan was a peasant girl from north-east France who claimed to have visions of Michael the Archangel, Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret, commanding her to liberate France from the English and enable the king's coronation.

The French desperately needed a hero to rally the beleaguered nation, and rumors abounded that Joan was the culmination of several prophecies predicting her rise. She arrived and met the king, making a great impression on the court. She was then subjected to three weeks of interrogations by a group of clerics who finally declared her genuinely 'of God' and not the devil.

Gilles was placed in charge of the army accompanying 'The Maid' to Orleans. He was instructed as follows:

"...before the army began the march on Orleans Joan gave a series of orders which were perfectly in line with her own thinking but totally against current practice. First she got rid of the regimental whores; they were given twenty four hours to marry or quit. Secondly she forbade swearing or blasphemy… Thirdly all the soldiers were to go to confession. Finally there was to be no pillaging or terrorisation of the populace. All food obtained from the local peasants was to be paid for."The army seems to have followed these guidelines. Gilles would go on to support Joan, take her side during several disputes and come to her rescue on a handful of occasions.

Together they managed to take the fortification of Saint-Loup on May 4. This was followed by a victory at the fortress of Les Augustins on May 5.

“Joan’s very simpleness and directness appealed to him. For her part she had every reason to be grateful to him. He had saved her twice; she could turn to him in a difficult situation …On May 7 they took the fortress of Les Tourelles.

… Perhaps even more important to Gilles was the magical world in which Joan lived, half heaven, half earth. When he rode and fought with her he became part of a living legend, a world of romance and literature come to life.”

"Joan was hit in the shoulder by an arrow from a crossbow while trying to place a ladder against the fortifications. Gilles caught her and removed her to a safe distance. He helped take off her armour so that the wound could be dressed ... Joan then returned, with Gilles, to the fight."On Sunday, May 8, the English and French armies drew up against one another and stood for an hour before the English turned and rode off - the siege was officially over.

Later that day Joan, Gilles and the others left to go to the king. On June 9, they returned in triumph to Orleans. From there they set out for more battles and had a successive series of victories, finishing by June 18.

“Gilles and the other commanders could be forgiven if they were drunk with their own success and filled with a religious or superstitious awe of this peasant girl who had brought them victory. In nine days they had reversed the whole balance of power. There can be no doubt that by this time Gilles was fully committed to the Maid. She gave him the most exciting, the most fulfilled period in his life.”On June 19, the army returned to Orleans. From July 1 to 16 a series of towns surrendered, including Reims - wherein the coronation of the king took place, on Sunday July 17.

At twenty-five years old Gilles was made Marshal of France.

The decline

Joan wished to continue campaigning but the king prevaricated and only minor skirmishes took place. In September the army attacked the gates of Paris but was driven back; Joan was shot in the thigh with a crossbow and dragged to safety by Gilles. The French suffered heavy losses and the king called for retreat.

By Sept 18 an agreement was made with Paris, followed by a truce with the English. Three days later the royal army was disbanded and prestigious honors given; there was to be no more campaigning.

That autumn Gilles' daughter Marie was born. He was beginning to experience financial difficulties after years of lavish spending and paying for armies. He sold one of his castles for funds which led to angry quarreling with his grandfather.

In 1430 Gilles took one of his fellow compatriots hostage, later freeing him for a ransom.

"Gilles had not lost his taste for pure banditry either. He regularly held merchants and travellers to ransom like a common highwayman. Nobody was exempt. He organized an ambush against Yolande d’Aragon herself… Gilles and his men attacked part of her escort and stole their horses and some of her baggage."In May of that year, Joan of Arc was captured by a Burgundian faction and given to the English. The truce had been called off and she was taken in the city of Compiegne. She was put on trial for heresy and found guilty (a year later she would be burned at the stake).

“While Gilles returned to the pursuits of his youth Joan had been taken prisoner, tried and condemned to death. There is no evidence that Gilles showed the slightest concern for her fate.

… “We next hear of him at Louviers on 26 December 1430. Much has been made of the fact that Louviers is not far from Rouen where Joan was being held, and it has been suggested that he was contemplating a desperate rescue attempt. Again there is no evidence for this. What he was in fact doing was buying a horse for one of his men, and borrowing the money to do it…”

Joan had lost her political expediency; neither the king nor Gilles made any effort to help her. During the summer of 1432 the English attacked Lagny:

On November 15, 1432 Jean de Craon died. Although Gilles was formally heir, his grandfather's sword and breastplate were left to his brother Rene de la Suze - a symbolic showing of disapproval."On August 10 Gilles attacked the besieging English forces with his usual vigor and Bedford was obliged to withdraw. Without Joan there to restrain him Gilles allowed his men to pillage and plunder as they always had before. Gilles had won an important victory that was to bring him almost as much renown as Orleans, but it no longer seemed to interest him. He never showed any taste for full-scale battle again. On his return to Champtoce he found his grandfather preparing for death."

The murders

With the war over, the king and court contented themselves with peaceful pursuits and entertainment; Gilles' services were no longer needed.

Any sadistic, psychopathic urges he'd experienced over his lifetime had been alleviated through controlled-violence: banditry, raiding, kidnapping for ransoms, feuding, and military expeditions. These things were now at an end and there was no one left to control him or curb his appetites - they were all dead or gone. He was fully master of his own dwindling fortune and affairs; he hated his wife who lived apart from him, and ignored his daughter. All that was left to occupy him was time and his own desires.

According to his later confession, he stated that the murders began in the year his grandfather died, about 1432 - 1433. The first murders took place at his Champtoce estate, then carried on when he relocated to Machecoul.

There were countless children orphaned from the war, poverty-stricken or desperate for employment from a rich lord; all of them were easy prey. At first, Gilles relied on his cousins Gilles de Sille and Robert de Briqueville to procure children for him. The first known case was a boy named Jeudon taken by the cousins, never to be seen again; they later claimed he had found work as a 'page'.

Testifying later on an accomplice declared:

“ ...that the said Gilles de Rais, in order to practise his libidinous pleasure and unnatural vices on the said children, both boys and girls, first took his member in his hand and stroked it until it was erect, then placed it between the thighs of the said girls, rubbing his member on the bellies of the said boys and girls with great delight, vigour and libidinous pleasure until the sperm was ejaculated on their bellies.

He declared that before perpetrating his debauches on the said boys and girls, to prevent them from crying out, and so that they should not be heard, the said Gilles de Rais sometimes hung them by the neck with ropes, with his own hand, from a hook. Then he would take them down and pretend to comfort them, assuring them that he wished them no harm, but quite the reverse; that he wanted to play with them, and in this manner he prevented them from crying out.

He further testified that the said Gilles de Rais sometimes committed his vices on the said boys and girls before wounding them, but rarely; other times, and that often, it was after hanging them up or before other wounds; other times it was after he had cut, or caused to be cut, the vein in the neck or the throat so that the blood gushed out; and other times it was as they were dying; other times it was after they were dead and their heads had been cut off, while there remained some warmth in the body.”After, or during the sexual assaults, Gilles killed the children or had others (servants, cousin) kill them. The general methods were: decapitation, slitting throats, dismemberment, breaking necks with a stick, or the use of a special sword.

“When the said children were dead he kissed them and those who had the most handsome limbs and heads he held up to admire them, and had their bodies cruelly cut open and took delight at the sight of their inner organs; and very often when the said children were dying he sat on their stomachs and took pleasure in seeing them die and laughed …

He apparently took more pleasure in the sadistic brutality of violence than even the sexual assaults:

Many parents handed over their children so that they could "work" for de Rais, and were compensated and placated with soothing lies. Despite rumors and concern, nothing was done; Gilles de Rais was a powerful man and these were merely peasant children who merited no investigation.

In Machecoul, between 1433-1434 he founded a personal chapel called the "Chapel of the Holy Innocents". His lavish spending continued on this new project, as did the sexual corruption of several choir boys.

In 1434, nearly bankrupt, Gilles traveled to Orleans to stage a production. It was the tenth anniversary of the siege of Orleans and he intended to produce a play to commemorate the event. To fund this new project and others of extravagance he began to sell off properties, take loans, sell personal possessions and pawn goods. He also began buying on credit.

His family took steps to try and reign in his finances, but to no avail. He turned to Jean V of Brittany; Jean V began lending Gilles money so that he had pretext to take his properties along the border. Jean V could not legally purchase them, but did so through proxies while allowing Gilles to slide deeper into debt.

Throughout all this, the murders continued:

When Gilles began to sell off his border-properties he had the bodies removed first. In one scenario:

Alchemy & Black Magic

As he neared bankruptcy, Gilles became increasingly desperate for money. Living in a very credulous time, he turned to the arts of alchemy and black magic to conjure funds.

It began with borrowing a book on alchemy from a knight; then paying a goldsmith to convert a silver mark into gold. The goldsmith promptly got drunk and failed in his task.

Gilles was not deterred; he employed a priest named Eustache Blanchet to seek out practitioners of alchemy. Several ridiculous encounters with various con artists ensued, and at one point Gilles wrote a pact meant for the devil which he signed in his own blood.

Blanchet found a man called Jean de la Riviere who staged two bogus attempts to 'summon the devil' and then took money from Gilles, promising to return and who was never seen again.

When Blanchet traveled to Italy, Gilles insisted that he find a master of alchemy. He returned with Francois Prelati a young, handsome man who made bold claims and promised success. Prelati tried numerous time to summon the devil or demons in order to exchange vows for gold. Unsurprisingly, all attempts failed. In one example:

Nearing the end

The experiments and invocation attempts continued, only by now Prelati had somehow convinced Gilles to stay away during the actual ceremonies. He continued to deceive Gilles by claiming that a demon named "Barron" appeared during the rituals Gilles was absent from; 'Barron' offered advice and answered questions.

In August, Gilles and his entourage traveled to see Jean V; he killed two boys before arriving. Sometime during this period, Jean V appointed Jean de Malestroit to collect information on Gilles. After their meeting, Gilles would go on to kill another three boys.

In December 1439 - Charles VII's son Louis came to visit. Before his arrival, Gilles and his servants destroyed any evidence of their invocations and 'black magic'. Gilles was growing increasingly paranoid and did not trust the king of France, so he moved back to his Machecoul property (located in the duchy of Brittany).

By now rumors and news of Gilles crimes were spreading:

By now Gilles was in dire financial straits, so he decided to repossess his old castle Saint-Etienne-de-Mer-Morte; it had been purchased by Jean V's treasurer (Le Ferron). He took the castle with the help of sixty men and imprisoned Le Ferron's brother (a priest) in the dungeon. This act was considered an indirect attack on the Duke of Brittany, and it gave Jean V the pretext he needed to take Gilles' properties.

Jean V imposed a massive fine he knew Gilles could not pay, and as such his properties were forfeit to the Duke. Gilles moved back to French territory, and in the meantime Bishop Jean de Malestroit ordered an official inquiry into Gilles de Rais, due partly to his treatment of priest Le Ferron.

Gilles would go on to kill at least another four children before de Malestroit published his findings:

Trial

Jean V had his brother in France occupy Gilles' french property, driving him back to Machecoul (in the duchy of Brittany).

On September 13, Jean de Malestroit issued a summons for Gilles, conjointly with Jean V. Two days later a posse arrived and demanded Gilles surrender; they read the warrant and he surrendered peacefully. His accomplices Prelati, Blanchet, Poitou and Henriet were also arrested; his two cousins had already fled. They were all taken to the city of Nantes.

Two inquiries and trials were to be held simultaneously for Gilles: one secular and one ecclesiastical.

He was summoned to the civil (secular) court on charges of murder and illegally repossessing a castle. His hearing before the ecclesiastical court would deal with religious matters and the charge of 'heresy'.

The civil court heard evidence from various witnesses until October 8. That same day, several also gave evidence before the ecclesiastical court. In the second court all concerned parties - secular and religious - were in attendance and the full weight of the charges was read.

It was then that Gilles realized the magnitude of the situation. Previously he had believed it was mostly in regard to repossessing the castle; he had entertained the notion of somehow maneuvering his way out. Now he reacted: he denied the competence of the court as well as all accusations; he withdrew previous statements and refused to take any oath.

On October 13 the public trial began and the formal indictment was read. A portion of it:

"Bluebeard"

The depravity of his crimes shocked everyone and he became notorious even in his own time:

Conspiracy theories

"He testified that he had heard the accused Gilles say that he took more pleasure in the murder of the said children, and in seeing their heads and limbs separated from their body, in seeing them die and their blood flow, than in having carnal knowledge of them."As for disposal of the bodies:

“Asked as to the place where they were burned, he answered in the room of the said Gilles …

Asked in what manner, he answered in the fireplace in the room of the said Gilles, with great logs of wood, by placing faggots on the dead bodies and then lighting a huge fire. The clothes were placed on by one in the fire and held in it, so that they burned more slowly and did not make such a bad smell.

Questioned as to the place where the ashes were thrown, he answered sometimes into the cesspit, other times in the moats or other hiding places…”

This was to be the pattern of behavior over the next seven years. Another accomplice was brought into the fold, an old woman named Perrine Martin and known locally as "The Terror". The circle of insiders expanded from his cousins to include servants Poitou and Henriet.

Rumors began to circulate about missing children. At first the theory was that children were being kidnapped to pay a ransom to the English for Gille de Sille's brother. Slowly, word crept out ... the mother of one murdered child told another woman "that it was rumored that the Sire de Rais had small children taken so that he could kill them".

Many parents handed over their children so that they could "work" for de Rais, and were compensated and placated with soothing lies. Despite rumors and concern, nothing was done; Gilles de Rais was a powerful man and these were merely peasant children who merited no investigation.

In Machecoul, between 1433-1434 he founded a personal chapel called the "Chapel of the Holy Innocents". His lavish spending continued on this new project, as did the sexual corruption of several choir boys.

In 1434, nearly bankrupt, Gilles traveled to Orleans to stage a production. It was the tenth anniversary of the siege of Orleans and he intended to produce a play to commemorate the event. To fund this new project and others of extravagance he began to sell off properties, take loans, sell personal possessions and pawn goods. He also began buying on credit.

His family took steps to try and reign in his finances, but to no avail. He turned to Jean V of Brittany; Jean V began lending Gilles money so that he had pretext to take his properties along the border. Jean V could not legally purchase them, but did so through proxies while allowing Gilles to slide deeper into debt.

Throughout all this, the murders continued:

"… the said Guillaume Hilairet declared that about five years previously [i.e. 1435] he heard a certain Jean du Jardin, who lodged with Messire Robert de Briqueville, say they had found a pipe full of dead children at Champtoce."In October of 1437, Gilles began to panic about incriminating evidence on his property. Worrying that his brother and others might seize his Machecoul property he had evidence removed by his cousin:

"He ordered Gilles de Sille and another of his men, Robin Romulart (Petit Robin), to dispose of the bones of about forty children ‘from a tower near the lower halls of the said castle’. While the work was going on Robert de Briqueville … arranged a peep-show for two noble ladies in the district, who were allowed to watch the operations in progress."Three weeks later his brother Rene de la Suze and Andre de Laval-Loheac seized and occupied Machecoul to prevent its sale. They found two skeletons but servants denied any knowledge of them.

When Gilles began to sell off his border-properties he had the bodies removed first. In one scenario:

"According to the evidence given by Henriet, they only had two days to complete the task before the bishop arrived. There were some forty bodies hidden in the tower. These may be assumed to be corpses of the children who died in the first wave of killing after the death of Jean de Craon…"There was not enough time to burn the bones, so they were removed to another location to be burned. Gilles demanded that four others accompany him:

"… to the tower of the castle of Champtoce, where the bodies and bones of several dead children were to be found, to take them and put them in strong chests and to transport them to Machecoul; all of which was done... And they found in the said tower the bones of thirty-six or forty-six children, which bones were dried up and he could not remember the exact number."They traveled to Machecoul where the bones were taken to Gilles' personal room and burned in his presence. The ashes were then thrown into the water pipes of Champtoce.

Alchemy & Black Magic

As he neared bankruptcy, Gilles became increasingly desperate for money. Living in a very credulous time, he turned to the arts of alchemy and black magic to conjure funds.

It began with borrowing a book on alchemy from a knight; then paying a goldsmith to convert a silver mark into gold. The goldsmith promptly got drunk and failed in his task.

Gilles was not deterred; he employed a priest named Eustache Blanchet to seek out practitioners of alchemy. Several ridiculous encounters with various con artists ensued, and at one point Gilles wrote a pact meant for the devil which he signed in his own blood.

Blanchet found a man called Jean de la Riviere who staged two bogus attempts to 'summon the devil' and then took money from Gilles, promising to return and who was never seen again.

When Blanchet traveled to Italy, Gilles insisted that he find a master of alchemy. He returned with Francois Prelati a young, handsome man who made bold claims and promised success. Prelati tried numerous time to summon the devil or demons in order to exchange vows for gold. Unsurprisingly, all attempts failed. In one example:

"... they stayed there, sometimes standing, sometimes sitting, sometimes kneeling so that they might adore the demons and make sacrifices to them, for almost two hours, invoking demons, making all efforts to invoke them diligently, the said Gilles and the present witness reading in turns from the said book, waiting for the demon they had invoked to appear but … nothing appeared on that occasion."At one point Gilles and Prelati "attempted invocations every day for five weeks, but never with any success." A typical example is as follows:

"When they arrived at the field the said Francois made a circle with the aid of a knife with crosses and characters, as he had done in the room in the castle. And having set light to the coals the said Francois forbade the witness to make the sign of the cross and enjoined him to step inside the circle as he himself did. And both of them being in the circle, the said Francois made the invocations."

Regarding the connection between Gilles' murders and attempts at black magic:

"It is essential to realise that Gilles’ paedophilia and homicide were quite distinct from his alchemic and satanic practices. They coexist but they do not connect. There is no evidence that Gilles ever indulged in human sacrifice, although he did later supply parts of the bodies of his victims for Prelati’s ceremonies. Gilles would have continued to abuse and murder children whatever the circumstances. Only financial necessity made him indulge in demonic practices."

Nearing the end

The experiments and invocation attempts continued, only by now Prelati had somehow convinced Gilles to stay away during the actual ceremonies. He continued to deceive Gilles by claiming that a demon named "Barron" appeared during the rituals Gilles was absent from; 'Barron' offered advice and answered questions.

In August, Gilles and his entourage traveled to see Jean V; he killed two boys before arriving. Sometime during this period, Jean V appointed Jean de Malestroit to collect information on Gilles. After their meeting, Gilles would go on to kill another three boys.

In December 1439 - Charles VII's son Louis came to visit. Before his arrival, Gilles and his servants destroyed any evidence of their invocations and 'black magic'. Gilles was growing increasingly paranoid and did not trust the king of France, so he moved back to his Machecoul property (located in the duchy of Brittany).

By now rumors and news of Gilles crimes were spreading:

"It was being openly said that Gilles was a child murderer and practising magic. The local populace had no idea of the nature of Gilles’ sexual crimes. They imagined that he was writing a great book in his own hand with the blood of the children he had killed. When the book was complete he would then have the power to take any stronghold he wished and he would be invulnerable. Gilles was already becoming the ogre of fairy tale and the foundations of the future legends were being laid."Gilles was unraveling. He killed four children that December; by May 15 there were another two recorded murders, and likely many more unnoticed.

By now Gilles was in dire financial straits, so he decided to repossess his old castle Saint-Etienne-de-Mer-Morte; it had been purchased by Jean V's treasurer (Le Ferron). He took the castle with the help of sixty men and imprisoned Le Ferron's brother (a priest) in the dungeon. This act was considered an indirect attack on the Duke of Brittany, and it gave Jean V the pretext he needed to take Gilles' properties.

Jean V imposed a massive fine he knew Gilles could not pay, and as such his properties were forfeit to the Duke. Gilles moved back to French territory, and in the meantime Bishop Jean de Malestroit ordered an official inquiry into Gilles de Rais, due partly to his treatment of priest Le Ferron.

Gilles would go on to kill at least another four children before de Malestroit published his findings:

"We make known … frequent and public clamor first reached our ears, then the complaints and declarations of persons of good character and discretion …

… and by their depositions have learned among other things, which we hold for certain, that the nobleman, Gilles de Rais, knight, lord of the said place and Baron … with certain of his accomplices had slaughtered, murdered and massacred in the most odious fashion several young boys, and practiced the vice of sodomy, which he did oftentimes and oftentimes had caused invocations of the devil to be made … that the said Gilles had committed the above-mentioned crimes and other kinds of debauch …"

Gilles last recorded murder took place in August. Despite the charges including 'human sacrifice' to the devil - that act was in fact not practiced:

"There is however only one record of human remains being offered as part of Prelati’s invocations… According to Henriet again, Poitou took the hand and heart of a child, which had been placed in a glass and covered with a cloth, and left it on the chimney-piece of the room where Gilles and Prelati made their invocations."

Trial

Jean V had his brother in France occupy Gilles' french property, driving him back to Machecoul (in the duchy of Brittany).

On September 13, Jean de Malestroit issued a summons for Gilles, conjointly with Jean V. Two days later a posse arrived and demanded Gilles surrender; they read the warrant and he surrendered peacefully. His accomplices Prelati, Blanchet, Poitou and Henriet were also arrested; his two cousins had already fled. They were all taken to the city of Nantes.

Two inquiries and trials were to be held simultaneously for Gilles: one secular and one ecclesiastical.

He was summoned to the civil (secular) court on charges of murder and illegally repossessing a castle. His hearing before the ecclesiastical court would deal with religious matters and the charge of 'heresy'.

The civil court heard evidence from various witnesses until October 8. That same day, several also gave evidence before the ecclesiastical court. In the second court all concerned parties - secular and religious - were in attendance and the full weight of the charges was read.

It was then that Gilles realized the magnitude of the situation. Previously he had believed it was mostly in regard to repossessing the castle; he had entertained the notion of somehow maneuvering his way out. Now he reacted: he denied the competence of the court as well as all accusations; he withdrew previous statements and refused to take any oath.

On October 13 the public trial began and the formal indictment was read. A portion of it:

"… that during the said fourteen years or thereabouts Gilles de Rais, the accused … to wit in an upper room where he oftentimes retired and passed the night, he killed 140 children or more, boys and girls, in a treacherous, cruel and inhuman fashion … he committed the abominable sin of sodomy … and abused them against nature to satisfy his illicit, carnal and damnable passions, and that afterwards he burned or caused to be burned in these same places the bodies of these innocents, boys and girls, and had the ashes thrown into the cess-pits of the said chateux …

… that during the said fourteen years, more or less, the said Gilles has held discourse with magicians and heretics: that he solicited their aid several times to carry out his purposes; that he communicated and collaborated with them, receiving their dogmas, studied and read books concerning their forbidden arts…"

The indictment insisted Gilles crimes began in 1426 (six years earlier than his confession), possibly for political reasons: undermining Joan of Arc's accomplishments and the French victories against the English.

Gilles continued to refuse to answer any charges, refusing four more times even on the 'pain of excommunication'. He was then formally excommunicated.

Two days later he suddenly recognized the competence of the court and admitted to the charges - except for the invocation of demons.

Witnesses were called and five of his accomplices testified, followed by another fifty witnesses.

By the 20th, Gilles was again refusing to comment. The next day he was brought to a room to be tortured (a rarity for someone of his social standing). He asked for a twenty-four hour delay and it was granted.

The next day Gilles made his confession as a scribe wrote out his statement. He admitted his crimes and dated the first murders to 1432.

"Asked by Pierre de l’Hopital where had learned to commit such crimes and who had led him to them, he replied ‘that he did them in accordance with his own imagination and thought, following no man’s counsel, but his own, solely for his pleasure and carnal delight, and with no other end in view’. Pierre de l’Hopital found this difficult to accept …"

"Despite all arguments to the contrary, despite the frequent incomprehension of his judges, Gilles insisted at all times that he had neither been guided nor influenced in his crimes, that he was totally responsible for the form which they took. He knew that they sprang from the depths of his personality."

The next day, on October 22, Gilles made a full confession before the assembly.

He justified himself by stating he had been spoiled as a child and never learned boundaries or the 'habits of virtue'. He bemoaned his lack of discipline and made a great showing of contrition all while instructing parents to teach their children 'good habits' and keep a watchful eye over them.

The day after, the confessions of his servants (and accomplices) Poitou and Henriet were heard in civil court. They were condemned to death.

On the 25th, Gilles was condemned to death. He was readmitted to the church and asked to give his religious confession to a monk, which was granted. He appeared again before the civil court which confirmed his earlier fine (by Jean V) - that was to be paid by selling his goods and property.

On October 26:

"As the fire was lit he was hanged. Shortly after he expired his body was removed from the flames and laid out by four noble ladies of the town. He was pampered and privileged to the end. Poitou and Henriet were shown no such consideration; they were burned to a cinder and their ashes scattered.

Prelati, who was condemned to perpetual imprisonment, managed to escape, but was hanged later for further crimes. Blanchet was fined 300 ecus and banished for life. Perrine Martin, ‘La Meffraye’, hanged herself in her cell."

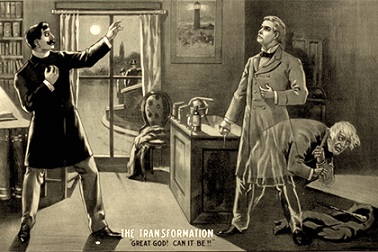

"Bluebeard"

The depravity of his crimes shocked everyone and he became notorious even in his own time:

"Within a short space of time Gilles passed into legend. His story became mingled with that of Bluebeard ... As the myth developed, the sadistic homosexual elements disappeared, to be replaced by stories of abducted girls and murdered wives."

Conspiracy theories

Some have put forward a theory that Gilles de Rais was innocent and was framed by enemies in the court and church, suggesting this was to obtain his property and money. However, such a scenario seems unlikely.

By the time of his trial Gilles was virtually bankrupt. Buying or obtaining his property through proxies would have been simple, and he had little by way of personal goods. In addition, his accomplices made full confessions and corroborated one another's stories. There were also the two noble ladies who witnessed the removal of bones and countless others whose children had gone missing through Gilles or his associates. The sheer number of disappeared children - local to Gilles and never seen again - provides good reason to believe in his guilt.

Gilles had a large fine he was unable to pay and in consequence all his property was forfeit - meaning there was no need to frame him for murdering children. Joan of Arc had been burned at the stake as a heretic and Gilles could be brought up on charges of heresy and witchcraft, which would ruin his reputation and provide a pretext for punishment without falsifying murder.

Lastly, Gilles provides us with the proof himself. If charges were false he could have blamed his actions on 'evil forces' such as "the devil". But he continued to insist "that he did them in accordance with his own imagination and thought, following no man’s counsel, but his own, solely for his pleasure and carnal delight, and with no other end in view."

What this shows is that he was aware of his own sexual deviation and the psychological impairment which drove him to sadistic impulses; there was no outer cause, it came from within. Even for his time, which was incredibly violent, they were not familiar with serial killers who killed for their own pleasure, something recognized in modern times. Gilles de Rais was simply a predecessor of men we are familiar with today, such as John Wayne Gacy and Jeffrey Dahmer.